My father, Andreu Ribera Llorens, was born in 1893. His first marriage was to Mercedes (Mercé) Casamada Rosinyol, and they had a son named Félix (1921-1983 ). But Mercé died in 1922 at a very young age, and my father married her sister Manuela (‘Manolita’) Casamada Rosinyol (1907-1997). Apart from me, they had two children, Andrés (1931-2017) and Jose Maria (1934-2023). (See the Ribera family tree since the 18th century https://pixabay.com/illustrations/youtube-video-icon-red-play-button-1495277/, maintained by Felix Gubert Gubert.)

The Civil War began in 1936 when I was eight years old. My childhood, which until then had been so wonderful, ended at that moment. The death of my father, who was the person I loved the most, put an end to all my happiness. They killed my father with five other men after imprisoning them in the basement of the Palamós Town Hall, which was then in a building on the Paseo de Palamós in a building by the name of Can Muntaner, where the Hotel Trias is now. They were killed on a day when the warship Canarias came to bomb Palamós. They were taken to Treumal, where later there was a house where Carmen and Mel Lord lived, and there they were buried in a nearby forest.

THE TWO GRAND RIBERA HOUSES

The Ribera family had stately homes in Palamós. The great Casa Ribera was built in about 1895 by built by a “Master of Works” named Salvador Bota Palia. The iron beams of the Ribera house come from Gustaf Eiffel of Paris. It was built during the time of my grandfather, Félix Ribera Cabruja (1861-1940) and his sister Cecilia (‘Celia’) Ribera Cabruja (1866-n/d). There was also the ‘Casa Ribera’ with the tower seen in the center of the photo, where my stepbrother Félix and his wife Asunción Serra Torrent (1921-2010) lived.

When the Civil War began in 1936, I was eight years old. The so-called militia kicked my grandparents out of Casa Ribera, and they came to live with us. After my father was killed, we went to live in my grandfather’s house, Juan Manuel Casamada, in Barcelona in a large house on Calle Pau Claris and Calle Valencia. My grandparents, Felix Ribera Cabruja and Concepció Llorens Maso, left Palamós by boat with my stepbrother Felix and my aunt and went to France. From there, they went to live in San Sebastián, which was then part of National Spain under Francisco Franco.

When the war ended, my grandparents returned to Palamós with Felix and my aunt, and they lived in the modernist Casa Ribera with the tower since the bombings badly damaged the other Ribera house. My parents and I went to live in a house in Carre de la Creu, which goes up to the Padró de Palamós. After the war, there was no food, and that house had a garden where we cultivated potatoes and other vegetables.

CHILDHOOD

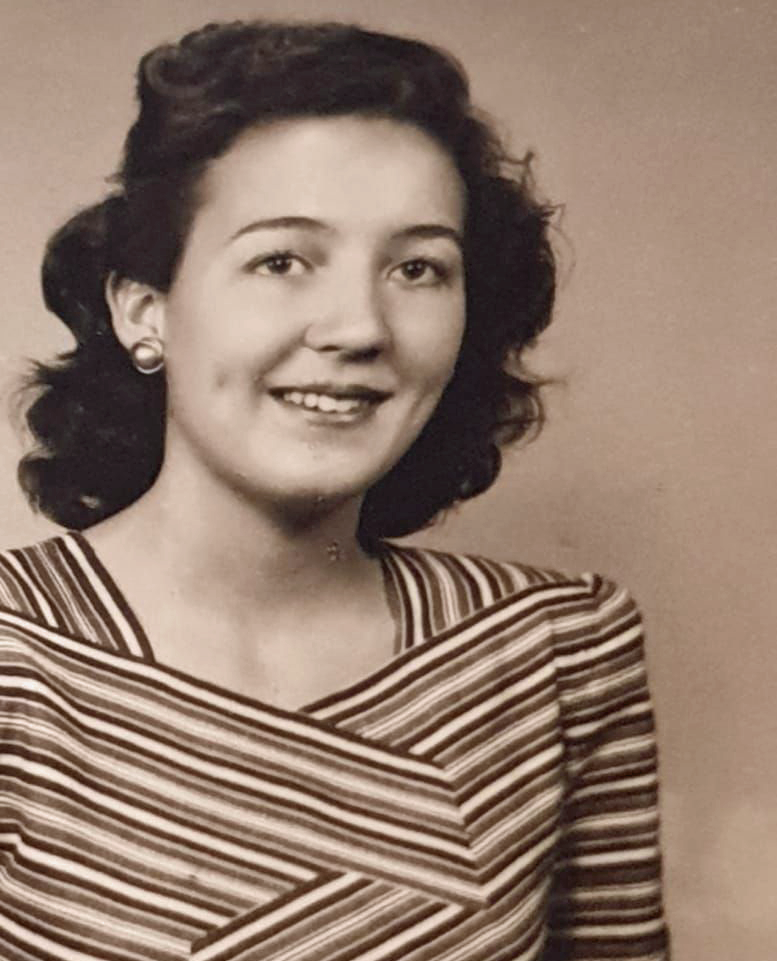

I was born on 19 August 1928 in Palamós. My education began with the nuns of the order of Carmelites at a school on the corner of Notarias and the street where the church is in Palamós. I have good memories of those years. But when I was 13, I went to study in Girona, also with the Carmelite nuns, and those were difficult times because the nuns were very strict and had strange habits and ways of thinking. There, I met Rosa Maria Pou, and, to this day, 82 years later, we remain best of friends and often speak with one another. Back then, when the nuns would see us together on the playground, they separated us and would send us inside to classes. I don’t know what they were thinking; probably that we were becoming lesbians! Luckily, I was only there for a year.

Because of the difficulties I had with the Carmelite nuns in Girona, my mother took me out of school and had me study independently from the nuns and under the guidance of Father Enrique Jorda. I was allowed to study this way because I was the daughter of a person killed in the Civil War. In that way, the government paid for my studies and tuition. When I finished my studies, I was examined at the Girona Institute, and I passed everything very well except for mathematics, which has always been difficult for me to understand. In my independent studies, I had several instructors, depending on the topic, and I especially remember Sister Peya, who was one of my best teachers.

ADOLESCENCE

After finishing high school, I took the State Exams in Barcelona and passed them with good marks. I then entered the University of Barcelona to study Philosophy and Letters, specializing in Literature and Romance Languages (that is, languages derived from Latin, such as Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese). I wanted to study English, but Franco was allied with Hitler, and they did not allow that language to be studied. Franco totally prohibited Catalan. So I had to study it secretly at night. I went to the house of a Catalan teacher who was the daughter of a Republican. I attended those classes in secret twice a week with several other women.

During my university years, I lived with my grandfather, Juan Manuel Casamada. Those were wonderful years. My grandfather became friends with all my friends, and he gave me a lot of freedom. The only exception was that I could not return from parties alone; I always needed to be accompanied by a friend. After having many sons and daughters, my grandfather was widowed. So, he went to the Monastery of Monserrat to study for two years, and he then became a priest.

One day, my grandfather was on a bus speaking badly about Franco and some boys, probably Falangists, heard him and took him to the police station. There, the chief said, “How horrible! No one has ever brought me a priest! What can I do?” So, my grandfather, very diplomatically, suggested that the police chief take him to the high priest at his church. And so the chief did, and, of course, the high priest did nothing to him.

I had several suiters during my college years (from 18 to 21). I fell deeply in love with one who was a mixture of Yugoslavian and Italian. But he was politically radicalized, and his attitude scared me. He left with his parents for Venezuela, and before leaving, he asked me to marry him. We would have had to get married through a notary public. It seemed like a big leap into the void, and I didn’t do it.

COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE

When I walked to the university from my grandfather’s house, I would pass by the pharmacy on Balmes Street. A very handsome young man named Pelayo Pagés Vilar would be there, and he’d make every effort to catch my attention. During that time, his parents, Pelayo Pagés Belleville and Maria Vilar Moner, went to the United States to stay with their daughter, Carmen Pagés Vilar, and husband, Melvin Lord, in the city of Tampa, Florida. Pelayo Sr. had a wonderful time. He spent a lot of time in the Cuban Quarter playing cards and smoking Cuban cigars. His wife Maria, however, suffered from migraines and didn’t go out. She had an awful time. When they returned, Pelayo Sr. and I became good friends and often went to the theater together. I remember seeing great movies with him, like Gone with the Wind and The Great Dictator. Pelayo Sr. would say, “Whenever I go to a movie, I learn something.” It was a great excuse to go to the theater often.

After three years of courtship, Pelayo and I were married by my grandfather Juan Manuel Casamada, and within a year, Pelayo Pagés Ribera was born in 1954. Three years later, Joan Pagés Ribera was born (in 1957), and in 1964, my daughter Mercedes Pagés Ribera was born.

FROM PHILOSOPHY AND LETTERS TO PHARMACOLOGY

My father-in-law Pelayo managed the Vilar Pharmacy in Palamós, which was located on the Calle Mayor in front of Pastisseria Collboni. It was founded by Juan Vilar Danés, father of my mother-in-law, Maria, who was originally María Vilar Moner. She had a sister, Carmen Vilar Moner, who lived on the other corner of Calle Mayor above Sastreria Rafel, and a brother, Juan Vilar Moner. Pelayo ran the pharmacy for many years, including those of the Civil War. Later, Juan Vilar Moner graduated as a pharmacist and wanted to take charge of the business that his father had started. So, Pelayo moved to Barcelona and opened a pharmacy on the corner of Calle Aribau and Carrer de la Diputación. He lived with his wife María, my mother-in-law, and his two children, Carmen and Pelayo, at Carrer del Consell de Cent 240, Pal 1º.

PAGÉS BELLEVILLE PHARMACY

Over time, my father-in-law Pelayo grew older and developed a very delicate heart. His son Pelayo, my husband, lacked the capacity to study a career that would allow him to maintain his father’s pharmacy operations. It occurred to me that I could save the pharmacy, knowing that my father-in-law would be very happy. And that’s what I did, and he was indeed very happy when I told him my intentions. After my father-in-law died in 1956, I was still studying. So, we paid a salary to a pharmacist who was a friend of my sister-in-law, Carmen. That pharmacist worked at a laboratory, and she used her pharmacy degree as if she were the owner of our pharmacy because there had to be a pharmacist with a degree. But she would only come if she had to sign some necessary documents.

One day, the Director General of the health department called the pharmacist and me to his office. He scolded us, saying that what we were doing was not allowed. We were really scared. I then decided to tell him the truth, and I explained everything to him. He sat there quietly and listened to my story. When I finished, he was very attentive and got up and patted me on the back. He then put the complaint against us, which was on top of a tall pile of papers, under everything. He told me, “These complaints will be processed, and a time will come when the one at the bottom, yours, will rise to the top. Things do not happen quickly, so yours will not come up right away. But you must hurry and finish your degree because if this complaint comes up and I’m not here or another person processes it, then your pharmacy will be taken from you.” Fortunately, I was almost finished with my degree, but I still hurried even more. And soon I finished my degree. So, in the end, the pharmacy was put in my name.

I did not have a vocation as a pharmacist. My vocation has been in a completely different direction, and I had to make a great effort to dedicate myself to being a pharmacist. I had to make a complete mental switch, and, in the end, I found a sense of helping people and having a special friendship with doctors. It was a question of psychology. I did it in a very convincing way.

At the time when my father-in-law and I had the pharmacy, there was more done in pharmacies, including the preparation of formulas provided by doctors. Doctors back then were also wiser than now because they knew the specifics of formulas. We did not create the formulas ourselves but rather processed the ones given to us by doctors. Grandfather Pelayo, as we called him, did have a vocation and intelligence with which to invent some medicines, and he was very successful with those medicines that he made through a laboratory.

All our children participated in the pharmacy work. My daughter Merce was great at running errands for us. She knew how to get around everywhere in Barcelona. She would take medicines to people if it was an emergency or go shopping for something we needed. Our sons, Pelayo and Joan, were in charge of processing the insured prescriptions because the pensioners did not pay anything, and others paid only a small percentage. Those insurance forms had to be delivered every month, and they had to be sent to Madrid. And since it took so long, we advanced the money, and sometimes it took three months for them to pay us.

Albert Buxeda was also in the pharmacy as an assistant. He was a man who worked at the Prat Pharmacy in Palamós for many years. He was young then and always very efficient. During the Civil War, he was a Republican soldier. At the end of the war, there was a horrible campaign against those who had been part of the so-called ‘Reds,’ and they were not given jobs when the war ended. Buxeda was a great person, but the pharmacist Prat fired him for being on the side of the Republicans during the war. Then, my father-in-law Pelayo, who was a great person, very honest, and had Republican ideas himself (although he was not one of the Reds who killed people), offered him a job in his pharmacy in Barcelona. So, Buxeda moved to Barcelona, and there he got married and had a daughter. He stayed with us at the pharmacy until he retired and then moved back to Palamós.

We had many adventures in the pharmacy, which I recount in my oral history that accompanies this brief account of my life. But I do want to mention here an important part of our lives. And that is that at home, we often had young family members stay with us. Marilee, daughter of Carmen and Melvin Lord, was with us for a year. The change she made at that time was extraordinary. My nephew Andrés also came to stay with us because his parents no longer knew what to do with him. I found him a teacher, and since then, he always tells me that it did him a great deal of good. I believe that doing things with love and affection and trying to understand people helps things work out in the end.

REFLECTIONS

Many things have gone well for me. It is because of my feeling of love towards people. A person has to do things that come from your heart and, well, from your head, too. I sometimes think that there are things that I should have done differently, even though, at the time, I thought I was doing them correctly. I was unable to dedicate myself to what truly fulfilled me: literature and philosophy. Instead, I also tried to look for something in the pharmacy that would give my life meaning. The most important thing, I believe, is to love people and not be selfish with yourself. Give of yourself. I believe it is the key to everything and what has come to me unexpectedly at the moment. I think that what makes it all worthwhile is to be sincere and try to express in actions what one feels. That philosophy in action is what I have just explained about my life in this brief story.