RETURN TO WASHINGTON, DC

In 1958, at the age of 46, Mel was hired by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank. The family rented an attached house on Cleveland Avenue near the Washington Cathedral.

They brought with them Carmen Cajide as a housekeeper from Caracas. She had traveled alone from Galicia by ship, paying the captain for her passage with a saffron bouquet. She was working in the Spanish Embassy and was referred to Mel by one of the officials. She traveled with my mother and children on the ship that sailed from Caracas to Miami via Curacao, a Dutch Caribbean island, and Habana, Cuba. She traveled with us as our ‘aunt’ and was given U.S. residency through Mel’s Spanish Embassy contacts in Washington, DC. My mother changed her name to ‘Carmela’ since there were already two other Carmens in the family, herself and ‘Carmencita.’ She remained with the family, in one way or another, for the remainder of her working life and was like a second mother to me.

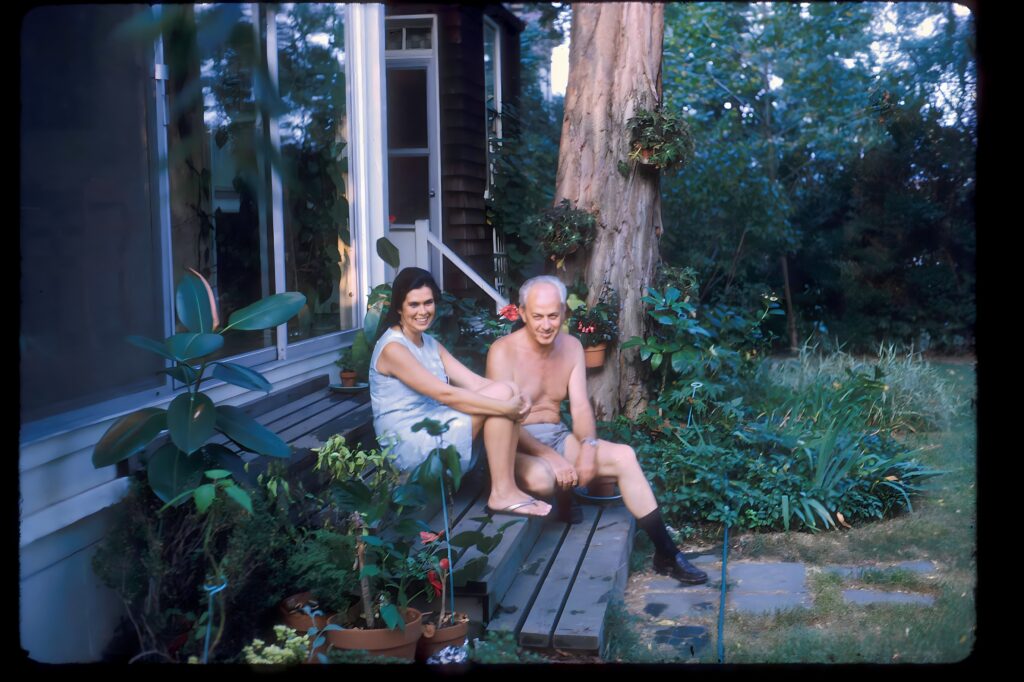

After a year’s search, Carmen and Mel bought the house at 3204 Klingle Road, NW, also near the Washington Cathedral. It was to become the best home they were ever to have, and Carmen told me later in life that the biggest mistake they ever made was to sell it in 1971, 12 years after having bought it in 1959. The place had originally been the location of the farmhouse of the Klingle family that lived in the Tregaron Estate. Klingle Road was literally ‘Klingle’s road that went to Georgetown, the main town near the estate.

The main features of the house were the huge backyard, which Aunt Elizabeth and Tia Nina designed, and the large living room with the picture window looking out towards the backyard. The house was purchased for $27,000, and $5,000 was spent on renovations to tear down the living room wall and extend the room to what was a closed-in porch at the time, adding the picture window in the back.

The living room was on the west side of the house, and there was a formal dining room on the east side, with the kitchen in the back. In the dining room, Mel would sit at the head of the table and Carmen at the other end and press a floor buzzard whenever a course was finished, and new dishes were to be brought in. Montague would sit to Mel’s right, and Marilee and Carmencita would sit on the other side. Marilee went to finishing school in Switzerland and returned with impeccable manners. We admired the way she was able to cut up oranges, bananas and all kinds of other fruits with her knife and fork, and we laughed at the way she would chew each bite 21 times.

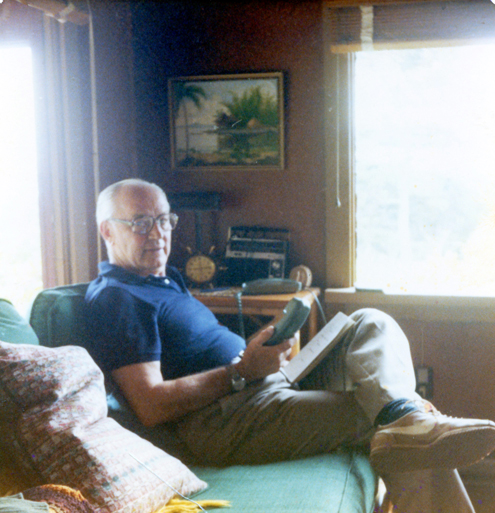

Mel loved to hold forth at the table because, he said, it reminded him of the early days with his father in the Philippines. Marilee and Carmencita would excuse themselves as soon as the desert finished, and Carmen would often pick a fight with Mel and go to her bedroom. That left me there, and Mel would tell me about his workday and other things that I don’t remember whatsoever because the talk would go on for about 45 interminable minutes. Later, I regretted not having listened to him more carefully because much of his work was so-called project analysis, and it was to be part of my work later in my career.

Mel and Carmen often went out to cocktail parties. When I say ‘often,’ I mean as often as seven days a week. Carmen loved parties; Mel did not, and I often wondered how he managed to work at the office all day and then go out in the evenings. He would sometimes call Marilee and me at home to check up on us and tell us that he was so hungry that he was eating the ice in his drink. They also had two outdoor parties every year for, as my mother said, “All the people that they had not had time to see yet.” That was, of course, an exaggeration. They had many close, good friends that they saw often and also good neighborhood friends. My mother told us, “You can choose your friends, but not your family.” It left us feeling rather forlorn, but later in life, I came to recognize that she was right.

For years, Carmen and Mel fought over her work. Mel wanted her to remain at home as a mother and housewife; Carmen wanted to work, remembering the fun times she had selling pottery in Tampa, Florida. In the end, Mel relented, and she went to work at the Young New Yorker Department of Lord and Taylor at Friendship Heights. She loved it and developed friendships with her boss, Sheila and Susi, whose family lived in the Tregaron Estate. Her grandfather had become a multimillionaire as a railroad magnate in Chicago, and she later married Burdette Wright, who was a CIA agent who worked with Mel.

Sheila’s first marriage was with a pianist, who she said beat her. Later, she married Tom Donaldson, a stockbroker who managed to lose all my savings in Pargas stocks and, more importantly, lost over $1,000,000 of Sherry Prado’s life savings, even though there was a bull market, which was all the money left from her husband, Juan Prado, after he died. Juan was an engineer and colleague of my father at IFC in the World Bank who had begun work at the same time as Mel, and Mel became the godfather of his children.

Mel spent much of his time with IFC, traveling on missions that would last several weeks. We once figured that at the height of his travels, he was gone for six months of the year. Carmen kept a huge ‘Jim Bowie knife’ and a set of Argentine ‘bolas’ under her pillow. We thought it hilarious since it would have been nearly impossible to swing those bolas in an enclosed space in the house. But there was little, if any, crime in the neighborhood other than that which Jed Palmer, our neighbor’s son, and I perpetuated (first, stealing items from glove compartments of cars that, back then, were never locked and; second, bombing the Chinese Embassy in Tregaron with ‘cherry bombs’ from West Virginia). Only once were the police called to our house because Carmen heard someone moving around outside. Well, they did also come looking for me after Jed and I ‘bombed’ the Chinese Embassy, but that’s another story.

In 1959, both Abuelita Maria Vilar Moner and Primita Maria Matas Pagés came to stay with us, Abuelita for a year and Primita Maria for 1-2 months. What a study in contrast! Primita Maria was kind, affectionate, and considerate. Abuelita, in contrast, was cruel, disagreeable, and indifferent to the feelings of others. To me, she was a tormentor. She would accuse me of being the cause of her migraines and would tell me that I was killing her and that when I returned from school, I would find her dead from the suffering that I had inflicted on her. The first time this happened, I returned from school convinced that I’d find her dead. Instead, she was high-spirited and gushing health, eating all the fruit that only she was permitted to eat without our 2-pieces-a-day limit because, she alleged, it was the only thing that quenched her thirst.

Another time, before leaving for school, she ranted and raved over her headache and assured everyone that she was dying. My mother called out physician Dr. Damien, asking him to rush over because her mother was at death’s door. An hour passed, and still no Dr. Damien, who only lived a few blocks away. She called him, and he told my mother that he was finishing breakfast and would come over sometime in the morning because he knew Abuelita well and was sure that she would survive. My mother laughed, and, from then on, they became great friends, and he started coming often to parties at our house. One day, I had to see him for an exam, and he called to say that he had suddenly become blind. That same morning, he committed suicide.

An example of Abuelita’s indifference to others occurred at Christmas, with tragic consequences. Carmen had bought a lovely scarf for Carmela. Abuelita said that she wanted it, so my mother relented and put her name on the box. Carmela knew she was to receive that gift, and when she saw it being given to Abuelita, she became fed up and left our service the next day. Rosario Aguirre came in her place and was a wonderful person to have in the household. But she could not replace Carmela.

Eventually, when my mother developed breast cancer, and my father was alone, Carmela returned. Later, after my divorce, she came over to my place weekly to clean and prepare food for no pay because I had no money at that time due to the high cost of childcare and alimony that I was paying. When Carmela retired and returned to Galicia, I would send her $50 every month; instead of using that money, she saved it all and returned it, in its entirety, when I went to visit her years later.

The final example of Abuelita’s oppression of the Lord family was her daily habit of standing at the entrance door at 6:15 p.m., when Mel would arrive from the office, to deliver a litany of evil acts that I had perpetuated that day. Inevitably, I would await my father’s visit to my room to scold me for all my misbehaviors. Much later on, he told me how sorry he was that he had criticized me but that he was powerless to go against Abuelita. The day that Abuelita returned to Barcelona, the entire Lord household could be heard breathing a sigh of relief.

SUMMERS IN SEAL ROCK

The Lord family traveled to Oregon twice to spend summers in Seal Rock. The first time was in 1958. On that trip, the family drove across the southcentral and northcentral parts of the country, staying overnight in motels. Both Carmen and Mel took turns driving, with the kids in the back seat. The second time, in 1962, was when Marilee and Montague both had recently obtained their driver’s licenses. On that trip, Mel did not join the family on the trip but instead flew to Oregon to join the family in Salem.

The trip across the United States was marvelous, though everyone fought tooth and nail the entire trip. Marilee was madly in love with a young man named Ramiro, and she would run into the restroom at each stop to write him a letter. Later, she would tire of him, and he came to our Klingle Road home back entrance one night tapping on my 2nd-floor window; when I went down to speak with him, he had a gun and was threatening to kill himself if he could not see Marilee. I told him that to get to Marilee’s room, he’d have to pass my father’s room, and for sure, he would get killed then. To that, he looked worried and left.

Marilee moved on to a relationship with a graduate student from the University of North Carolina whose name was Pedro. Ramiro, nevertheless, pursued her and followed her to Barcelona, where Tio Pelayo told Ramiro in no uncertain words to stay away from Marilee. Then he followed her and Tia Mercedes to Prullans, and while Marilee hid, Tia Mercedes, as well as her brother Felix, explained to Ramiro that Marilee no longer wanted to see him. For my part, the year before, I had lost my virginity to a buxom Peruvian girl named Rina and was feeling very fulfilled. I left for Oregon with little interest in returning to Rina and instead looked forward to new adventures.

Returning to the cross-country trip, we divided the driving among the three family ‘adults’ for 2-hour shifts because each wanted an opportunity to drive. Rosario Aguirre came with us, and I do not remember her saying a single word the entire trip. We dragged a Nimrod behind our convertible Buick. The Nimrod was a boxed trailer that would pop up into a tent to accommodate the four women, while Montague had his own ‘pup-tent’ separate from the Nimrod. We visited practically all the national parks from the mid-west to the West and covered the far south on the outbound trip and the far north on the return trip. When we arrived at each national park, we would build a fire, and Rosario would make us a ‘paella.’ It was a luxurious way to travel.

Two exciting events occurred on that trip. The first was when we were in Yellowstone National Park. After dinner, when it was getting dark, Carmen, Marilee and I went to a campfire talk held in the campsite by rangers to tell stories about the park. One of the stories that the ranger told us was that there was a mean old bear that they called Khrushchev. That name came from the premier of the Soviet Union between 1958 and 1964 named Nikita Khrushchev. He had a terrible temper and once removed his shoe in the United Nations to use it to bang on the table.

Well, when we were returning to our campsite, who should have appeared around our area but Khrushchev the bear himself! As we heard the claws of the bear walk in the forest, we quietly returned to the campsite and came upon Rosario sitting by the fire, which had gone out completely, with Khrushchev looking at her from the bushes! We took pots and pans and banged them repeatedly until Khrushchev lumbered away. We asked Rosario why she had not gone into the Nimrod, and she said that she was too scared to move. No doubt Khrushchev had smelled her paella and was coming over for a helping.

The second incident occurred at another campsite one night when the women were sleeping in the Nimrod, and I was sleeping in my pup tent quite a distance from them. In the middle of the night, we heard incredibly loud noises around our campfire. The women thought the animals would attack them in the Nimrod, and I thought it more likely that they would target my flimsy tent that was barely being held up by two sticks. Neither Mother nor I had any idea about animals or, rather, beasts.

In the earlier 1958 trip to Oregon, Mel’s father, Montague, flew to the United States from the Philippines and joined the family in Seal Rock for the summer. I have already described his visit earlier when chronicling his life. He died a year and a half later while Mel was on a mission in Argentina. Mel was unable to be with his father when he died, but his sister, Aunt Elizabeth, did arrive in time to be by his side.

The only person who knew anything was animal-loving Marilee. But she needed her contact lenses to be able to see, and, in the excitement, they were nowhere to be found. My mother told me to make a run for it and jump in the Nimrod. Well, I did, and I don’t think I ever ran so fast in my life. As I dove through the door, Marilee found her contact lenses and looked out. It was a single raccoon rummaging through the trash can and, of course, making a huge racket.

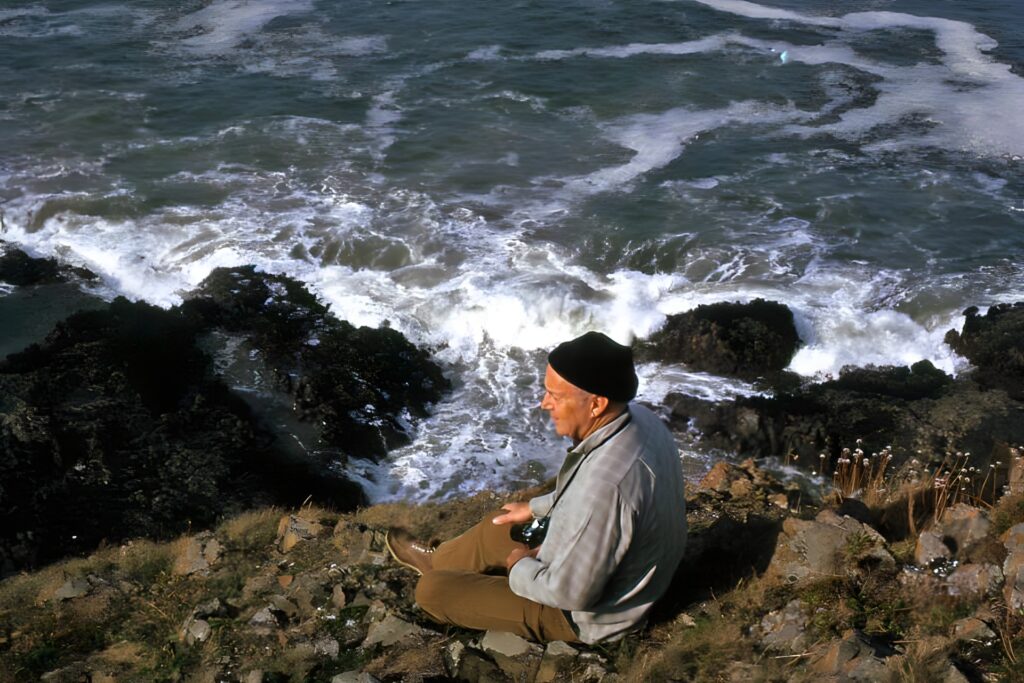

On the second trip in 1962, Mel felt free from his obligations to his father, and he introduced us to his sister, Dorothy, and her husband, Claire. On both trips, the family stayed with Aunt Elizabeth Lord and Edith Schryver in both their Salem home and Seal Rock. Mel loved them both, most especially Aunt Elizabeth, and they were very fond of Mel and his family.

LATER YEARS IN WASHINGTON, DC

The years 1962 to 1969 were tumultuous years for me. Years of adolescence and teen years. But this is the story of Mel. So, I will not go into those events in this biography. I have already deviated enough times with the Lord family adventures.

In 1969, Carmen had a mastectomy. By that time, Marilee and Montague had left for school, leaving only Carmencita in the household with Mel. Carmencita had become troublesome, and when she was found taking LSD, and Mel found her huddled into a closet, he sent her away to boarding school. Mel was left alone with Carmen and was completely devastated by her operation. Carmela, our housekeeper who had been driven from home by Abuelita, returned to be with the family, and she was a great support to Mel.

Years later, Carmela described the situation to me as a turning point in their relationship. Mel had always been the dominant one in the relationship. But when Carmen had the mastectomy, he became subservient to her, and in their relationship that followed, Carmen became the dominant one. I saw that change also, but Carmela was the one who noticed it first and was able to articulate the change.

Carmela also described to me Carmencita’s transformation after taking LSD as one that changed her character from a sweet to an exceedingly devious person. Carmela’s observation preceded Carmencita’s kidnapping of Carmen after Mel died when she and her husband Ahmed put all the family property in their names. Those events are documented separately from this biography.

In any event, Mel and Carmen continued in Klingle Road another year before putting it on the market at the instigation of Carmen. She wanted Mel to retire so that they could travel and enjoy the remainder of their lives while they were both active.

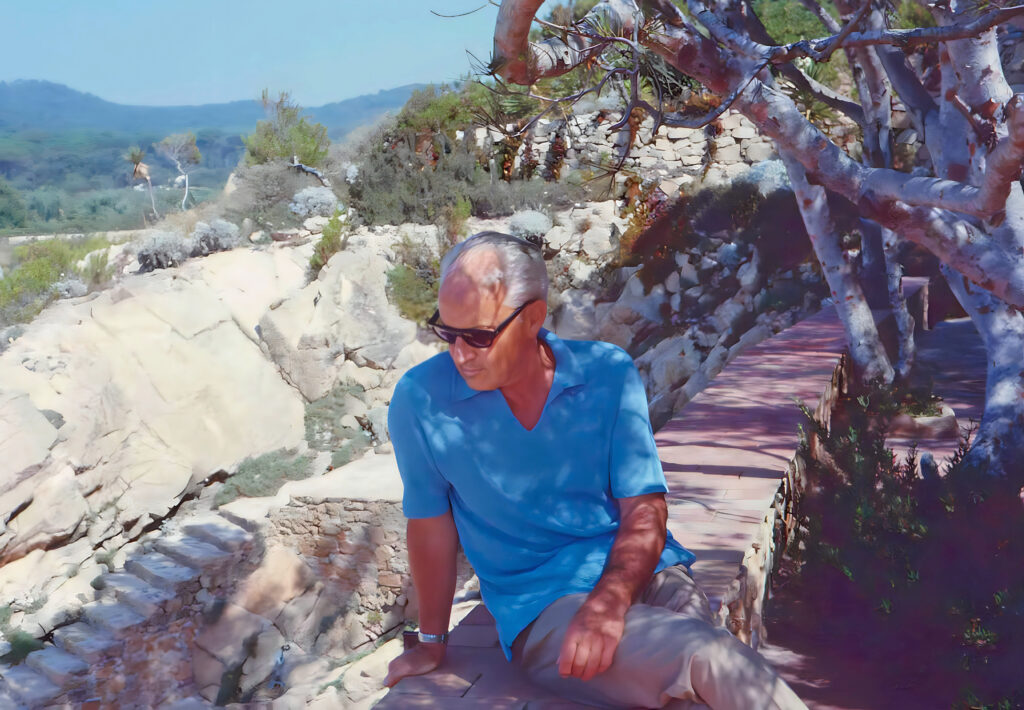

The family spent the summer of 1970 in Palamós and had a wonderful summer together. Carmen was recovering and would take powerful drugs that knocked her out for hours during the day. They bought a top-floor apartment in Palamós along the Paseo at Pere el Gran, which they kept for several years before Felix (father) Gubert found them the apartment in 1975 that was being newly constructed in the Faro of Palamós. They kept that as their magnificent residence in Palamós for the rest of their lives.

RETIREMENT

In Mel’s final 2 to 3 years at the World Bank, he was given a plush assignment in Jakarta to support Bapindo, a development bank of the Indonesian government. Carmen and Mel moved to a large estate within the city. Marilee’s husband, George, had taken an assignment with FAO in the country, so they moved into the compound with Carmen and Mel. They all had a wonderful time together and regularly traveled on weekends to Bali.

During this time, Mel had an affair with his secretary. He had been sharing secretarial services with a World Bank colleague, and they competed for her attention. Marilee soon discovered Mel’s affair when she traveled with him to Manila, and he bought a diamond-studded watch that never appeared on Carmen’s wrist. She knew then, for sure, that the affair was in full bloom.

When Carmen and Mel returned to Washington, Mel developed an ameba in his liver and, thinking that he would die, confessed his affair to Carmen. She did not forgive him for his transgressions and refused to touch him afterward while he was hospitalized. Later, I jokingly said that I’d bet he wished that he had died, and he got mad and told me to mind my own business.

But with Carmen, she and I were soon laughing about it, as she told me that her relationship with Mel had gone stale and that this incident had renovated a spark in it. Perhaps she said that to cover her hurt since, after all, she must have felt slighted by him. But she openly spoke about it and kept us all in the loop. Later on, Mel gave me good advice that I have always remembered, although, at the time, I thought it was quite gross the way he said it. I repeat it here in a somewhat more polite manner, and it was that “a dog does not do his business in his backyard.” Words to live by.

After Indonesia, Carmen and Mel rented an apartment in Madrid, near our old tower apartment in Paseo Rosales. They were next to their very good friends, Betty and Tasio Rodriguez, also a World Bank retiree. Carmen and Mel bought an old stone house in the small town of Ortigueira in Asturias, where Betty and Tasio also had bought a house. But they seldom visited the place and practically gave it away to some locals who had been the property’s caretakers. In Washington, DC, they bought a small apartment in Foggy Bottom with a view of the Potomac River.

So, they divided their time among four properties located in Palamós at the Faro; Seal Rock, Oregon; Madrid; and Washington, DC., plus Ortigueira in Asturias. They also went on many cruises throughout the world. But, as they grew older, they would remain on the cruise ship and seldom visited countries where the ship stopped. It appeared as though they were trying to recover their happiness in the places where they had most enjoyed their lives, namely, Palamós, Oregon, Washington, and Madrid. Mother told me that the biggest mistake they ever made was to sell the Klingle Road home, where they had been so happy.

Both suffered from alcoholism, perhaps Carmen more than Mel. She liked to say that she didn’t eat but rather just drank to keep herself pickled. But it became a way of life for them, more and more as the years went by.

ENDINGS

Mel began to develop Alzheimer’s in 1994, and he tragically spent the last ten years of his life with a progressive loss of memory and lack of cognitive abilities. He became very dependent on his immediate family and increasingly socially isolated. I remember that at the beginning of his Alzheimer’s, we visited Richard Davies, of whom I have already spoken. Mel’s colleagues and friends from work were there. Mel remained next to me and would only speak with me. It was as if he felt uncomfortable and unsafe to be with people outside of his immediate circle.

Carmen insisted on caring for him without assistance, except from the immediate family, and she took to drinking heavily and being unable to control her frustration with Mel. Once, I was in their Palamós Faro apartment with Marilee’s son Christopher, and we were sitting at the dining room table with Mel. Chris and I were talking about development issues since he was interested in that topic at the time. Mel tried to participate in the conversation and became confused in his words, and had difficulty expressing himself. Carmen was in the kitchen, next to the dining area, and said, “Mel, don’t you see that Montague and Chris are speaking? Don’t interrupt them!” He very clearly responded that what she said had deeply hurt him.

Their friends, Maria and Joaquin Llavero, lived next door, in the apartment above the garage where Carmen and Mel kept their car. Maria told me that at night, Carmen would drink and yell at Mel. She asked me to take them away. I repeatedly asked Carmen to put Mel in a caretaker facility, but she insisted that she wanted to take care of him. She said that he had taken care of her all her life and that she did not want to take care of him now. But it was apparent that she was incapable of giving him all the care and attention that he needed. Carmen and I ended up not speaking with each other. Carmen drank a great deal. She had always drunk excessively but increased her consumption during this period. Mel would also drink a great deal of wine because he did not remember how much he had already consumed. Carmen did not attempt to stop him since drinking must have calmed him. Carmen did not want to have anyone in the apartment to clean or cook, largely because it would affect her ability to drink liberally, in my view. As a result, they both ate extremely poorly, and one never knew how long the food that was served had been around.

My sister Marilee visited them regularly and greatly helped with Mel’s caretaking. She was happy to have them in Palamós and enjoyed taking care of them, though I saw that it greatly saddened her. There was also a retired taxi driver and his wife who drove them around. So, their life in Palamós was as good as it could have been without the necessary caregiving and professional services. But Carmen decided that she wanted to go to their small apartment in Washington, DC, instead. So, Marilee arranged for their trip there, and their grandson Julius Gwyer met them at the airport to pick them up once they arrived in the United States.

Years later, my aunt, Tia Mercedes Ribera, talked about why they had moved to Washington, DC since Marilee had told her that she wanted to take care of them in Palamós, and they had a reasonably good life there with family and friends. I believe the reason was that Carmen was extremely competitive with Marilee. Although she undoubtedly appreciated Marilee’s help, she did not like having her as an equal and having Mel enjoy her company the way that he always did. In comparison, Julius was equally attentive to them, and Carmen was always close to him, as was Mel.

Years earlier, Carmen had wanted to establish a residency in Palamós, behind the church in the Plaza de la Iglesia. An apartment complex was being constructed, and she suggested that Carmen and Jose (Pini) Matas buy into the apartment complex with them, along with some of the other socially elite families in Palamós. Unfortunately, that proposal never succeeded. It would have been ideal for them.

The last ten years of Mel’s life were lousy for both him and Carmen, who eventually lost complete control. But Mel had a wonderful life; they both did, and it was only the last ten years that they both could have done without.

In the end, they were financially abused by their daughter Carmencita and her husband Ahmed, who, after Mel’s death, abducted Carmen and hid her in an undisclosed location in Washington state. At the same time, they took over her accounts and property. The abduction occurred during a residency in State College, Pennsylvania. They took her for a day trip and never returned. My nephews and I collaborated in finding Carmen. With the help of a former FBI detective, we located them in the basement of an apartment complex in a town called Vancouver in the state of Washington. The Pennsylvania state attorney wanted to prosecute Carmencita and Ahmed under felony charges for elderly abuse, but they had fled the state. We were able to get the Washington state court to take over Carmen’s well-being.

By then, much of the valuable property of jewelry and paintings stolen by Carmencita and Ahmed were gone, and the vast financial holdings previously held by Carmen and Mel were distributed among multiple bank accounts set up by Carmencita and Ahmed. We only were able to locate 42 accounts within the United States and none overseas. Much probably remained in their possession. All the real estate property had been transferred to Carmencita and Ahmed for $1 each, and we were able to restore the property to Carmen’s estate.

In the end, we were forced to reach a settlement with them to prevent the Federal and State governments from taking large portions of the estate to recover unpaid taxes. Large payments, nevertheless, had to be made to lawyers and the elderly management company that was assigned to the well-being of Carmen, as well as multiple unpaid bills left by Carmencita and Ahmed to Carmen’s residency in Pennsylvania and other places. Amazingly, Carmencita complained about all the legal and elderly care costs that were deducted from her final share of the estate, as was done with my share and that of my nephews. I do think that Carmela was right when she said that LSC had altered Carmencita’s brain.

It was a tragic ending for the family. Mel died in State College, Pennsylvania, on October 10, 2003, at age 90. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. Three years later, Carmen passed away at age 85 in a residency in Washington state on September 13, 2006. I visited her shortly before she died. She was feeble but still playing her ‘solitaire’ card games quietly, but with the shrewdness that I had found in her mother, Maria, shortly before she died in a residency in Barcelona. Indeed, when I had visited my grandmother for the last time in that residency when she was 97 years old, and I introduced her to my new wife at the time, she whispered to my wife as she leaned down to kiss her on the cheek, “Let’s see how long you last in this family!”. Like my grandmother, my mother took one look at me and, with her eyes glistening, said, “I knew you’d come back to me.”

My father’s passing was traumatic. I was informed of his death in State College and drove there with my nephew Julius. He had died, and Carmencita and Ahmed had told the nurses and administrative officers that we were not to receive any information about his death. I had already been there earlier by myself to visit him and found him completely drugged up and unable to be woken up from his stupor. It was a terrible way to say goodbye to him. When I left him and returned to my rental car, I broke down and cried uncontrollably. Now, years later, I can look at my father’s life as a whole and not dwell on those final moments. If he had his life to do over again, I’m sure he would have preferred for the early years of his life to have been easier to get through. But they made the man who was to become self-confident and able to reinvent himself whenever life dealt him a bad hand. And, with Carmen’s character of what she called extremes, he turned his life into a wonderful adventure.