This chapter covers the creation and operations of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during the Second World War to contextualize the material covered in the following two chapters on US clandestine activities in Europe and those of Melvin Lord in the Costa Brava. We begin with a brief overview of intelligence operations during the war, then highlight the most notable undertakings of the intelligence agency and their impact on the progress and outcome of the war. The chapter concludes with an explanation of how the OSS was dissolved and partially integrated into the new Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1947.

1.1. Definition and uses of intelligence

Secret service operations existed in many countries throughout the 20th century (Heaps, 1998). According to Scott and Jackson (2004), intelligence encompasses collecting, analyzing, and using information focused on identifying and interpreting threats directed toward a country, a group of states, or a given geographic area. Political leaders establish the objectives and limitations of their country’s secret services (Scott & Jackson, 2004).

An essential attribute of intelligence is the confidentiality of its operations. With the Second World War, once the conflict was over, the OSS reports were sent to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Some files related to foreign affairs were kept by the Central Information Department (CID), one of eight divisions in the Research and Analysis (R&A) branch of the OSS (Heaps, 1998). Confidentiality regarding the clandestine operations of government offices in countries like the United States and Great Britain was considered to be essential, even years after the termination of those activities (Scott & Jackson, 2004).

These restrictions made research on clandestine operations difficult for decades (Scott & Jackson, 2004). However, in the sixties, the demand for documentation by the civilian population increased in the United States, and in 1966, the Freedom of Information Act was approved by Congress. CIA personnel reviewed the documents of its R&A department to make them public, becoming the first national intelligence agency to allow access to its previously classified files.

NARA did not allow public access to OSS reports until the eighties and nineties for security reasons. When they did, they used volunteers and the latest media technology to facilitate access to information (Heaps, 1998). In the 21st century, some political events have also contributed to improving the transparency of intelligence documents, raising doubts among the civilian population about government conspiracies, such as the invasion of Iraq (Scott & Jackson, 2004).1

Access to intelligence archives is helpful for academic research. However, when working with these sources, one must consider the subjective nature of the reports written by undercover agents worldwide (Chalou, 1992). Their perspectives were subject to the limited tools available. According to Aline Griffith (Chalou, 1992), an OSS agent undercover in Madrid between 1943 and 1944, it was common to make vague descriptions or misinterpretations of events, for the most part, unconsciously. There were, of course, instances of purposeful manipulation of information by governments (Scott & Jackson, 2004).

Jackson (2003) notes that academic studies often link intelligence agencies with specific political ideologies. However, established guidelines on reporting procedures are used to minimize subjectivity in government reports. Intelligence agencies not only tried to inform political leaders, but from the Second World War onwards, they helped to shape international relations (Jackson, 2003). According to Aldrich (2000), the full development of intelligence services during the Second World War was possible because of the need to defend against new threats and the introduction of cryptanalysis (Scott & Jackson, 2004). The significant expansion of the American secret services could also have been determined by the perception of US weaknesses after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, given that the American navy was unable to decrypt Japanese naval communications (Jackson, 2003).

1.2. Background of the OSS

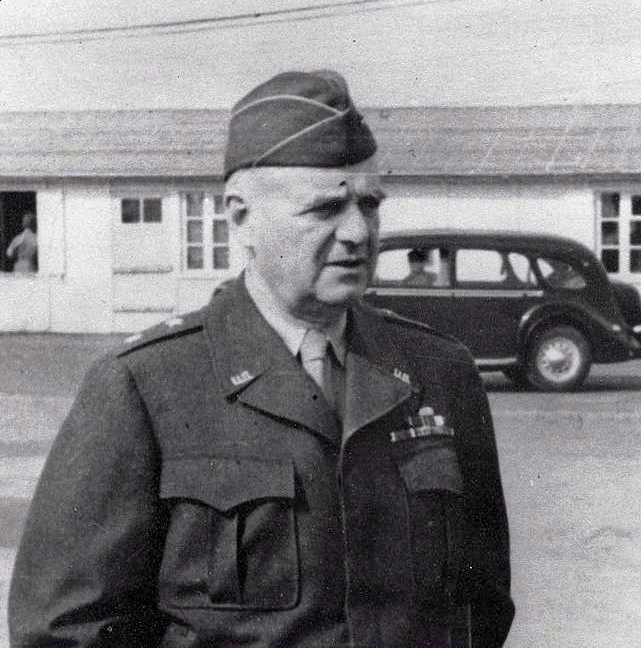

The Japanese attack on the American base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941, opened the way for President Franklin D. Roosevelt to create the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) of the United States of America (Villalobos, 2019). The OSS was established on June 13, 1942. According to OSS agent and later historian Richard Harris Smith (1972), the idea for this agency took shape during the New Deal in the 1930s.2 The person responsible for how it would operate was William Joseph Donovan (Dunlop, 1984)—nicknamed Wild Bill. He had been deputy attorney general of the United States between 1925 and 1929 and later created a law firm (Bradsher, 2021).

During the 1930s, Donovan formulated the concepts for team infiltration and clandestine operations (McWilliams, 1991); Belot, 2002; and Charles, 2005. Charles (2005) argues that the origins of American intelligence services reflected the operations of the Federal Bureau of Information (FBI) and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN). The FBN was created on June 14, 1930, to combat drug trafficking by exchanging information with European countries, Canada, Egypt, and Asian countries such as China, Formosa, and the Philippines. Commissioner Harry J. Anslinger, a foreign affairs and intelligence expert headed the FNB. He ensured the FBN would collaborate with the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL). Aslinger’s agents were trained to infiltrate drug cartels and to handle weapons (McWilliams, 1991).

The FBI had been established on July 26, 1908 (Bonaparte, C.J., 1908).3 During World War II, the agency was charged with German counterintelligence and was under the leadership of J. Edgar Hoover (Charles, 2005). At that time, Nazi spies, under the leadership of Frederick “Fritz” Duquense, were in New York and were suspected of starting fires in different cork factories (Taylor, 2018). Hoover created a Special Intelligence Services department to investigate those fires (Belot, 2002).

Following the cork company sabotages, Hoover’s men visited Great Britain between 1940 and 1941 to investigate the methods used by the British Security Service (MI5) and the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS).4 The FBI also surveyed police functions in times of national emergency in England (Charles, 2005). Officer Hugh H. Clegg, in charge of the mission, and his assistant, agent Lawrence Hince, studied cryptography, British foreign intelligence, and efforts to decipher the Axis codes (Charles, 2005). While the FBI was in charge of German counterintelligence, the United States Army gathered intelligence in Europe and Asia with their Military Intelligence Division, while the Navy monitored the Pacific with the Office of Naval Intelligence (Belot, 2002).

In 1940, William Donovan traveled to London with the same objective as the FBI: to learn about British Intelligence. However, he focused on the German Fifth Column, the population that sympathized with the Nazis. Donovan returned to Europe in December 1940 and again in 1941 to visit the Middle East to check the Mediterranean region’s economic, political, and military situation (Charles, 2005). He found that the support of the Allied forces was necessary to safeguard North Africa from an invasion by the Axis powers (Bradsher, 2021). Donovan also became interested in the English Special Operations Executive (SOE), which was charged with undertaking acts of sabotage in the occupied European territories. SOE maintained contact with the French resistance, the civilian population, and the political elites (Belot, 2002).

When he returned to the United States, Donovan proposed to Frank Knox the creation of a single Foreign Intelligence Service for the United States, under which all operations were to be centralized. Its model was the British system, established secretly and controlled by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (Charles, 2005).5 On July 11, 1941, the predecessor to the OSS was created and was known as the Office of Coordinator of Strategic Information (COI). It was directly linked to the White House and led by Donovan (Belot, 2002). Although there was a dislike between Donovan’s and Hoover’s men, the two services collaborated closely in their operations(Scott & Jackson, 2004).

1.2.1. William Donovan and the Office of Coordinator of Strategic Information (COI)

William Donovan warned the US government to prepare for the enormous growth of European armaments. In 1932, he traveled to Germany and was struck by the German army’s strong technological advances. In 1935, during the Second Italo-Sanusí War, he visited Mussolini and warned President Roosevelt that Italy would win the conflict because of its weaponry advantage. In 1936, Wild Bill entered Spain, which at the time was immersed in its own Civil War, and he informed the Chief of Staff of the United States Army about the technical advances of German war material supporting the Francoist army (Bradsher, 2021).

Because of his role as a trusted analyst, Donovan was ordered on missions from the White House in 1940, first to Great Britain and later to the Balkans and the Mediterranean (Charles, 2005). He returned convinced it was necessary to create an intelligence service in the United States, one that worked with the Allied forces. Although not belligerent, Franco’s Spain and Antonio Oliveira de Salazar’s Portugal had clear preferences towards the Axis powers. The colonies in North Africa were dominated by Vichy troops, collaborators of Nazism (Smith, 1972). Given these circumstances, the German’s potential to close the Straits of Gibraltar was great (Taylor, 2018).

Once the COI was created, it was divided into the Foreign Intelligence Service (FIS) and the Research and Analysis Branch (R&A). Robert Sherwood headed the FIS, and Dr. J.P. Baxter II the R&A (Belot, 2002). The Special Activities Goodfellow division was also created within the COI (named after its leader, Colonel Preston Goodfellow). William Donovan met in New York with the city supervisor of this division, Garland Williams, to establish the foundations of a new operations program that radically broke with the methods of war conducted until then.

Under the direction of supervisor Williams, the new COI agents were instructed to use various weapons and perform hand-to-hand combat (McWilliams, 1991). The British Special Operations Executive assisted Williams with a training plan to bring the agents to their full potential. They were to learn to parachute and conduct paramilitary exercises while developing aquatic skills and communication techniques. That training would be essential for the later activities of OSS detachments (McWilliams, 1991).

For the recruitment of agents, Ian Fleming, a high-ranking officer in American Naval Intelligence, had suggested to Donovan that he should hire intelligence officers who were between forty and fifty years old and shared the qualities of possessing absolute discretion, sobriety, devotion to duty, languages and extensive experience (Smith, 1972). Donovan rejected Fleming’s advice and promised President Roosevelt an international secret service of young officers who were calculatedly reckless, disciplined in courage, and trained for aggressive actions (Smith, 1972). This approach is the one that was used to shape IOC and OSS operations.

The IOC was dedicated to organizing subversive actions in North Africa. It sought to establish a US presence through arms and financing while establishing links with native African leaders allied with Germany and Spain. American intelligence used psychological and economic combat tools (Belot, 2002). In June 1942, Roosevelt dissolved the IOC and created the Office of Strategic Services, headed by William Donovan. The OSS was to maintain the IOC’s core principles, gather foreign intelligence, and conduct special operations (Charles, 2005). In its special operations, it supported, trained, and supplied European resistance movements with provisions; where guerrilla movements did not exist, they were to create them and thereby weaken the enemy’s war potential (Belot, 2002).

1.3. OSS Creation, Development and Initiatives

“Espionage is a strange netherworld of refugees, radicals, and traitors. There is neither room for gentility nor protocol in this work. Utter ruthlessness can only be fought with utter ruthlessness; honor, honesty, carefulness, and sincerity must be left to the fighting forces and the diplomats.”6

As mentioned above, the Office of Strategic Services was established on June 13, 1942. Its internal structure mirrored the British system, which focused on worldwide espionage missions. Donovan branched out, taking the British MI6 as a reference, into the new intelligence service: the OSS was thus divided into the Secret Intelligence (SI) branch and the Special Operations (SO) branch, both of which were responsible for sabotaging and coordinating with the clandestine movements in countries in where they operated. Both branches included (a) a counterintelligence section, responsible for recruiting and supervising agents while preventing enemy infiltration into the ranks of the OSS, and (b) a research section responsible for logistics, management, photography, research, and development, led by psychologist Stanley Lovell (Belot, 2002).

A Moral Operations (MO) branch was also developed within the OSS. It used different methods of influencing the Axis troops through “black propaganda psychologically” (García, 2007). To do this, falsified newscasts and military orders were distributed throughout enemy territories. The most effective activity of the MO was a black propaganda radio station established in London that sent information to Berlin. The OSS had, therefore, entered the “psychological warfare” stage (Walker, 1987).

The objectives of moral operations were to provide greater control over the direction and effects of the conflict while demoralizing enemy soldiers, an initiative that the Nazis had already promoted at the beginning of the war (Walker, 1987). Within these strategies of control over the population came the mass media, through which specific messages could be directed to a large audience via advertising, music, films, and other media. According to Sánchez, Iturbide, and Lizaso (2012), the OSS also used the “white psychology” within its troops, both to guide the selection processes and to treat the traumas caused by the Second World War. The officers of the Intelligence Agency also discovered that to keep their soldiers’ morale high, they had to learn to manage their leisure time (Sánchez et al. 2012).

One of the most confidential projects of the Office of Strategic Services, according to McWilliams (1991), was the research to find a “truth serum,” that is. This drug would make enemy prisoners reveal confidential information. The experiments with scopolamine, morphine, mescaline, or tetrahydrocannabinol acetate were unsuccessful, but they made use of marijuana to stun enemies more easily. It was not until 1953 that Lysergic Diethylamide Acid (LSD) was accidentally discovered (McWilliams, 1991).

The OSS differed from COI’s scope and authority for foreign intelligence gathering (Charles, 2005).7 While it too was part of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), unlike the COI that reported solely to the President, the OSS was supervised by the military. The constant oversight by the top brass of the US Armed Forces led the OSS to develop a more rigorous organizational and operation organization (Walker, 1987). According to Belot (2002), for the first time in US history, a secret organization dealt autonomously and globally with established functions, becoming deeply involved in regions considered strategically critical to the United States (Belot, 2002, 60).

Financial sources for OSS operations were extensive. They included the Tolstoys, the Romanovs, and Prince Serge Obolensky. Private sources of funding comprised such large corporations as Paramount Pictures and Standard Oil Company, with headquarters in Spain and Switzerland (Smith, 1972). However, they did not include the Rockefeller fortune in the oil industry since Nelson Rockefeller had broken with Donovan over control of propaganda in Latin America and had established his own espionage company named the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs to operate in that region.

Donovan sought to create an organizational environment where agents would coexist regardless of their ideological differences, nationalities, social class, culture, or gender. The OSS doctrine was therefore declared apolitical, and the organization worked as a team harmoniously and with a common goal (Cole, 1951). This concept was revolutionary. Although Roosevelt’s New Deal policies had fostered the development of a welfare state where American citizens were brought closer to an equitable income distribution, racism by government agencies increased disproportionately after the attack on Pearl Harbor (Galindo, 2008).

Roosevelt signed Order 9066 in February 1942 (Galindo, 2008), allowing Secretary of War Stimson to arrest and imprison without charge or trial anyone who was naturalized as Italian or German. Their homes and businesses could be summarily seized (Taylor, 2018). Likewise, Japanese Americans were interned in labor camps.

The Office of Strategic Services was one of the most important agencies created during the Second World War, and its membership grew to 13,000 by 1944.8 It dominated agent infiltration in Southeast Asia and surpassed British intelligence in Europe (Jackson, 2003).

1.4. The OSS in Europe and the Mediterranean

Nazi activity in New York was one driver for US involvement in Europe, but there was another important reason: British Intelligence Service (SI) agents discovered that the Nazis were financing several anti-war groups in the United States (Smith, 1972). One example was the America First Committee, which collaborated with and financed other organizations such as the National Council for the Prevention, Keep America Out of War Congress, Youth Committee Against War, and Minister’s No War Committee (Cole, 1951). These groups had members throughout the United States and used a variety of ways to promote their anti-war messages. The America First Committee argued that American ships should not enter the conflict zone and that humanitarian aid should not be sent to Europe (Cole, 1951).

The OSS gathered German know-how about atomic energy and other scientific advances in Germany. That information helped to attract scientists to the United States after the war (Belot, 2002), mainly to involve them in Operation Paperclip to gain access to German expertise in rocketry, missiles, and biological warfare. In Poland, when the USSR and other powers refused to help attacks such as those of the Warsaw Uprising, the OSS sent aid sothe Poles could resist the German invasion (Smith, 1972).

In the Balkans, some agents of the executive agency of Rabbi Nelson Glueck—a German Jew and agent of Penrose, who created the spy network among the Arabs of Transjordan—conducted suicide missions for the OSS and the English Special Operations Executive (SOE) (Rodriguez, 2015). The war in Yugoslavia was another place where OSS agents entered combat on the side of Tito and the partisan resistance, suggesting to some that the OSS had communist sympathies (Sidoti, 2004).

Although there were some members of the American secret services who had sympathies for communist doctrines, Donovan’s men had become involved in the battles in Eastern Europe because they perceived Tito’s troops as being brave and dedicated warriors fighting against a common enemy (Smith, 1972; Sidoti, 2004).

In France, the OSS’s Operational Groups (OG) unit trained and organized the Maquis movements of the French resistance. OG agents supported their guerrilla warfare tactics by providing training in unconventional actions that did not necessarily involve direct hand-to-hand combat (Hill, 2013). They also trained exiles from the Spanish Republic involved in the French resistance led by Charles de Gaulle (Smith, 1972). Moreover, when the Normandy landing was being prepared, Donovan created an operation named Jedburgh, whose members acted in small groups of three to support guerrilla activity (Hill, 2013).

In Spain and Portugal, clandestine networks helped Jewish refugees flee to the United States and other countries in the Americas. As stowaways, they traveled on ships carrying materials such as cork. Once on board, the passengers continued to be in danger since not all cargo ships were supported by the Spanish Republican cause (Taylor, 2018). On the North African coast, the first major American offensive occurred under Operation Torch and, in Chapter 3, we will describe how Melvin Lord participated in it.

1.4.1. Operation Torch

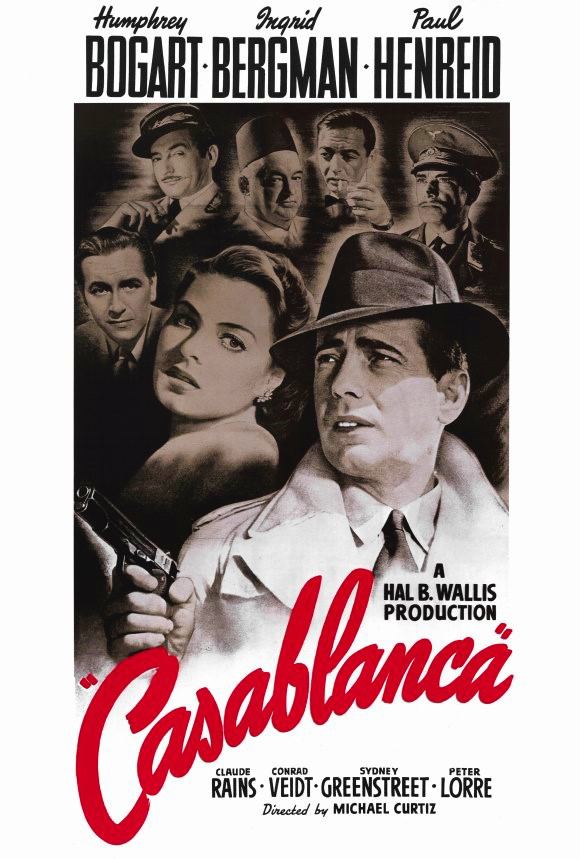

An economic agreement was signed between the United States and France on March 10, 1941. In it, the French colonies in North Africa, under the control of Vichy troops, would receive merchandise shipped from the United States. In return, the vice-consuls of William Donovan’s IOC would ensure that those goods did not fall into the hands of the Axis powers (Walker, 1987). However, the advance of German troops in North Africa jeopardized the agreement. Franklin D. Roosevelt dissolved the IOC in June 1942 and, a month later, decided that the newly created OSS would be in charge of preparing an offensive on the coasts of Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers (del Corral, 2013). That invasion took place on November 8, 1972 (Belot, 2002).

To prepare for the attack, American agents gathered information about the terrain, railways, and roads with the help of the French resistance in the area. The Gaullists were kept out of the preparations since the French had gained a reputation for having ineffective security measures, especially when under the influence of alcohol (Smith, 1972).

Operation Torch represented a new way of operating militarily because of its dual nature: on the one hand, the landing of Allied soldiers would be direct, similar to a traditional offensive; on the other, espionage and resistance operations were carried out. The latter activities included actions by the Moral Operations branch to demoralize the enemy through propaganda (Walker, 1987).

The conflict resulted in a large number of casualties on both sides, far more than the Allies had expected when preparing the offensive. The Americans and the British had been convinced when preparing the offensive that the French would welcome being rescued from Nazi Germany. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who led Operation Torch, did not trust the effectiveness of the offensive. The conflict ultimately ended in an Allied victory, as Jean Darlan, the admiral in charge of the Vichy armed forces, ordered a ceasefire after being blackmailed by OSS men (Walker, 1987).

The Anglo-American incursion curbed the expansion of the Afrika Korps military unit, which had been sent to North Africa a year earlier to reinforce Italian troops. It fulfilled its aim of securing access to the Mediterranean. Operation Torch, along with the battles of El Alamein in October 1942 and Stalingrad between November 1942 and February 1943, was considered a significant turning point early in the Second World War (Walker, 1987).

1.4. Dismantling the OSS

In October 1945, President Harry S. Truman ordered the Office of Strategic Services to be dismantled. He moved only its Research and Development (R&D) section to the State Department (Hill, 2013). Many academics who had been part of its ranks kept their positions as university professors, but others became part of postwar intelligence operations (Davis, 1998). The OSS had set a precedent for US intervention in international affairs (Smith, 1972). Other nations used General Donovan’s methods after the war and they were used extensively during the Cold War conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, which lasted from 1947 until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 (Jackson, 2003).

After several failed attempts to organize intelligence services, Congress created the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1947. The aim was to centralize all clandestine operations in a simple bureaucracy. Many professional military officers and civilian veterans who had served in the OSS during World War II were absorbed by the agency. The internal structure of the new agency was divided into two main operational divisions: the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC) and the Office of Special Operations (OSO). The first would deal with political subversion, and the second would manage espionage and intelligence gathering (Smith, 1972).

The CIA maintained the apolitical pragmatism of the OSS, as well as the mix of intelligence gathering and special operations. The profile of its agents was also similar: men with imagination and decision-making capacity, aggressive and with a high level of political knowledge. Although the new agency wanted to maintain the horizontal structure of the OSS, whereby agents could bypass the chain of command on certain occasions, this was not feasible given the large bureaucracy and its broader geopolitical scope. The new world order was characterized by fragile peace where science and technology played a critical role and nuclear disaster was an ever-present reality (Belot, 2002).

- Following the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, Prime Minister Tony Blair and President George Bush of Great Britain and the United States, respectively, were accused of distorting intelligence gathered by the secret services to justify the dispatch of troops to Iraq in April 2003 (Scott & Jackson, 2004). ↩︎

- Richard Harris Smith was the author of OSS: The Secret History of America’s First Central Intelligence Agency (1971). Heaps (1998) notes that, due to the privacy policies regarding classified information during the second decade of the 20th century, the files of the American intelligence services were not available for review, even by former high-ranking officials. Harris therefore had to use secondary sources and rely on his own recollections. ↩︎

- Order of July 26, 1908, signed by Attorney General Chaplies J. Bonaparte, in Washington, D.C. ↩︎

- Both were British secret services (Charles, 2005). ↩︎

- Frank Knox was the Secretary of the Navy and a close friend of Donovan. Through his influence in the White House, “Wild Bill” effectively conveyed his proposals to President Roosevelt (Charles, 2005). ↩︎

- Quote attributed to Donald Downes in his internal memoir for OSS Director Bill Donovan (Taylor, 2018, p. 99). ↩︎

- The JCS represents the country’s highest military leadership, which includes the Chiefs of Staff of the main branches of the United States Armed Forces (Roman & Tarr, 1998). ↩︎

- Shortly after the invasion of France by Vichy troops in 1940, the Foreign Office and the Special Operations Executive were created in Great Britain (Jackson, 2003). ↩︎