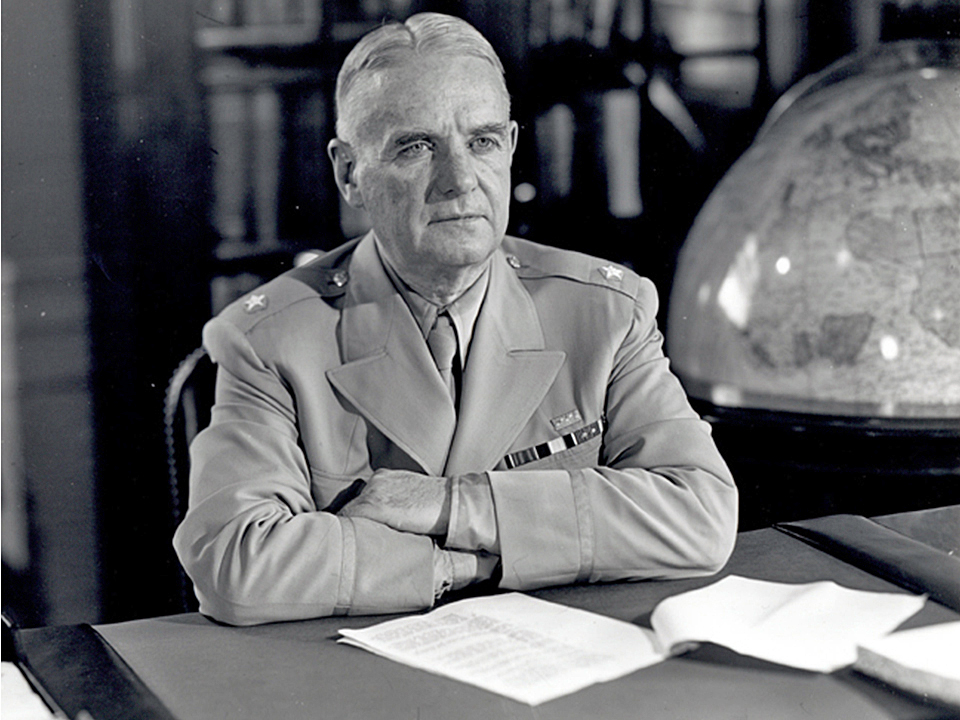

The interest of the Office of Strategic Services in Spain was based on US government efforts to halt the spread of Nazism, especially along Mediterranean areas (Smith, 1972). OSS objectives in Spain and Portugal were threefold: first, to gather information on possible Nazi coups or invasions; second, to gather data on the Spanish aid provided to the enemy side; and third, to collect work material that could be crucial if the Iberian Peninsula became a battlefield (Taylor, 2018). These objectives were merged into an operation called “Operation Banana”.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Sir Samuel Hoare, British ambassador to Spain, had been tasked with keeping the Spanish army away from the Axis powers. Hoare and the Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco, agreed to Spain’s neutrality if Franco could be assured that an Allied victory would not overturn his regime. Despite the agreement, in July 1942, the Allies intercepted a message indicating that Spain planned to join the Axis. Thus, the Special Operations Branch of the OSS was asked to infiltrate Spain, despite the risk that, if discovered, Franco could let the German army through the country and facilitate the invasion of North Africa and Gibraltar. Wild Bill gave his support, and agents moved into Spain to monitor the Francoist army and identify any Nazi military movements (de Monsabert, 1953). A few months earlier, in January 1942, as part of the IOC’s operations, Donovan’s officers had already entered the Spanish embassy in Washington to review official documents of the pro-Axis government of Spain. OSS reports warned that Hitler “owned Spain” (Smith, 1972). In Madrid, OSS operations focused on strategic deception and disinformation directed at the enemy while gathering intelligence on German weapons and covert operations the Nazis were conducting in Spain. The OSS also transported art treasures and valuables from Europe to safe havens in Latin America (Chalou, 1992).

The most critical areas where the OSS sent its agents were those bordering Spain, namely France and Morocco. Many agents of the Axis powers and pro-German officers of Franco’s army were given asylum in Morocco. There, the Nazis were establishing schools for saboteurs, who were to be infiltrated across the border between Spain and France (Smith, 1972). The expansion of Allied troops in Morocco during Operation Torch also allowed the United States to get closer to the Franco regime (Walker, 1987). As the French were collaborating with Germany, Americans infiltrated that country via Spain to monitor the movements of the Axis troops. OSS agents and local collaborators rescued Jews and other refugees through the established routes across the Pyrenees. Given its proximity to the mountains and the sea, the Costa Brava became one of the empicenters of OSS operations (Sánchez, 2003).

2.1. Dual strategies

In 1942, US President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill contacted Franco the Spanish dictator to inform him about the imminent Operation Torch. They hoped it would bolster Franco’s confidence in the Allies and keep Franco neutral in the conflict with Germany (Sáenz, 2009). As mentioned earlier, the OSS mobilized a large-scale infiltration of its agents into the country. It used both psychological and guerilla warfare methods that allowed agents to use political and military methods to bring about broad-based changes in the country.

Donald Downes began preparations of “Operation Banana” in 1943, without the support of the British and American embassies (Domínguez, 2018).1 It aimed to start a rebellion against Franco and reestablish the Republican government, thus ensuring the support of Spain on the side of the United States and Great Britain (Taylor, 2018). The operation failed since the agents sent to Andalusia from Morocco to establish contact with what remained of the clandestine government of the Spanish Republic were arrested by Franco’s police (Domínguez, 2018). Under torture, many confessed to having been recruited by Donald Downes and Arthur Goldberg. The US government had not authorized the OSS to carry out the operation, and it was forced to apologize to Franco and leave the agents to die at the hands of the Gestapo. Donovan agreed not to conduct subversive espionage operations against the Franco regime in its future operations in the country (Smith, 1972).

A year earlier, OSS intelligence operations had already initiated contact with the Maquis, the guerrillas in the French resistance. In Spain, this group included the anti-Franco guerrillas established during the Spanish Civil War. They helped map the Catalan coasts and presented reports on the Axis military defenses along the coast. One of the most extensive mappings was the military deployment in the Bay of Roses, which went from Cap de Creus to the Medes Islands (Sánchez, 2003). The information gathered by the Maquis helped to create routes for use by Jews and other refugees escaping from Germany and France. From the French-Spanish border, various passeurs (smugglers) and collaborators took the escapees to Barcelona, through the inland towns or the coast, and onward to Gibraltar, Portugal, or Casablanca, where they could eventually be sent into exile to the Americas (Sánchez, 2003).2

The OSS considered the Catalan coast one of the most dangerous areas of the country because of the large amount of Gestapo activity in that area. Diplomatic protection was non-existent, which forced many Allied agents to leave quickly when they were in danger of being discovered (Taylor, 2018). There were over six hundred German intelligence agents in Spain, along with many Italians and Japanese agents.3 Likewise, members of the OSS were warned that they should distrust their respective state departments and embassies. They were told, however, that they could trust Spanish citizens who had been on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War.

There were many double agents, and the OSS recruited Germans, Italians, and Spaniards who worked for the Gestapo (Chalou, 1992). Some of the companies infiltrated by the OSS included the American Petroleum Mission in Madrid and the cork companies Armstrong Cork and Crown Cork, with headquarters in Seville and the Costa Brava (Chalou, 1992; Taylor, 2018).

2.2. Role of the cork industry

During the Roosevelt administration, Secretary of War Henry Stimson argued that capitalists countries engaging in war needed to allow their businesses to make money from it (Feagin & Riddell, 1990). Many companies therefore supported the war effort. Those that initially refused, including the Armstrong Cork Company, were forced to do so by the presidential decree issued in 1942 by Franklin D. Roosevelt, according to which the manufacture of materials not essential to the war should cease (Taylor, 2018).

The American cork industries were clustered on the East Coast, the region most vulnerable to German sabotage. Saboteurs used shortwave radios in Long Island to send information to offshore German ships, including submarines. The government viewed the security of critical defense supplies in jeopardy, and the Federal Trade Commission accused Crown Cork and Armstrong Cork of conspiring to suppress competition. New federal laws prohibited the media from publishing information about cork and other materials considered strategic, as there was a danger that companies in this industry would undermine production capabilities in other industries dependent on cork (Taylor, 2018).

Three weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the American War Department summoned executives from Crown Cork & Seal and, later, Armstrong Cork Company to a clandestine meeting in Washington. Both companies had branches along the Mediterranean coasts. For the US government, their overseas operations offered a means of infiltrating agents into the territories of Spain, Portugal, and North Africa (Taylor, 2018).

Before the war, in February 1938, American newspapers reported that German aircraft were bombing northern Catalonia, endangering commercial exports. Among the affected areas were the cork oak forests and the towns of Sant Feliu de Guíxols and Palamós, both strategic to shipments from their ports (Taylor, 2018).

Armstrong Cork had branches in Palafrugell, Palamós, and Santa Cristina d’Aro (Museu del Suro de Catalunya, 2022). The company had an excellent reputation for employee loyalty, as they were provided with health and life insurance, overtime pay, and paid holidays. In Palafrugell, Armstrong Cork took over an old local company in the area, “Manufacturas del Corcho S.A.,” and the German national Kurt Walters began working there.4 As OSS agents, Melvin Lord and David Sanderson watched over Walters while working in the Armstrong Cork branch in Palafrugell to determine whether he had any links with Nazi intelligence.

2.3. Agents and training

“Very often in history […] the fate of nations has depended on the success of a small anonymous group, who have taken their lives in their hands to carry out an espionage mission to save their homes or to serve an ideal.”

Donald Downes, The Scarlet Thread (1953).

OSS agents were chosen for being intelligent men with different abilities and their ability to take appropriate initiative in wartime operations. However, the most important requirement was to master foreign languages (Hill, 2013). Military experience was also a plus in recruitment, although it was unnecessary in the OSS branches. Aspiring members had to pass a questionnaire showing high intellect, emotional flexibility, and tolerance for physical pain. People with traits that could attract attention were avoided.

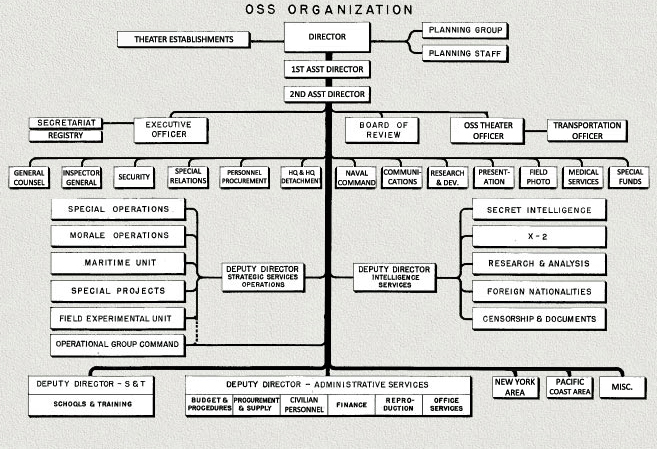

Since there were OSS branches dedicated to psychological warfare, such as that of Moral Operations (MO), progressive writers and figures from the world of entertainment in Hollywood and Broadway were recruited. Even persons with communist leanings were eligible for recruitment as long as they did not bring their ideology into their work. Nonetheless, some were found to be sending messages to the Soviet Union. There were also refugees from Nazi Germany and, therefore, already had strong democratic convictions against the Axis powers (Smith, 1972).

The Research and Analysis Branch (R&A) branch was comprised of intellectuals. They included economists, historians, geographers, other social scientists from prestigious universities (Heaps, 1998). Its members included Yale historian Sherman Kent, Coolidge philosopher H. Marcuse, and Harvard history professor William L. Langer (Belot, 2002; CIA, 2009).

One of the OSS’ first projects was to recruit a group of exiled Spaniards for future espionage operations in Franco’s fascist regime (Smith, 1972). Donald Downes, who joined the group in 1942, was in contact with Julio Álvarez del Vayo, the foreign minister of Republican Spain who had spent the war in exile in the US and proposed continuing the resistance through guerrilla warfare (Martín, 2024). Downes also established contact with Dr. José de Aguirre, a professor at Columbia University, and helped him be part of the Spanish government in exile in Mexico City (Smith, 1972).

Before Operation Torch, Downes began creating clandestine teams in case Franco entered the war in favor of Germany and its allies (Domínguez, 2018). By November 1942, he had recruited a team of Spanish agents, and they were joined by American communists who had fought in the Spanish Civil War as members of the Lincoln Brigade.5 They were to act in North Africa after the landings of Operation Torch, joined by Mark Clark’s Fifth Army (Smith, 1972). According to Donovan, the Marxist and Communist recruits were courageous in espionage and sabotage. They had experience from helping the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War, during which time they participated in the International Brigades.

Downes also sought recruits in the concentration camps of southern France and North Africa. There, he interviewed prisoners as potential agents. His formal proposal to the Allied headquarters was met with silence. He then withdrew his proposal, left the bureaucrats to debate his proposal, and went to the Sahara to help the prisoners escape. He took them to a clandestine school in an old village outside Algeria, where they were trained by two radio experts, the brothers of Puerto Rican descent, Michael and James Jimeneth, veterans of the Lincoln Brigade (Smith, 1972).

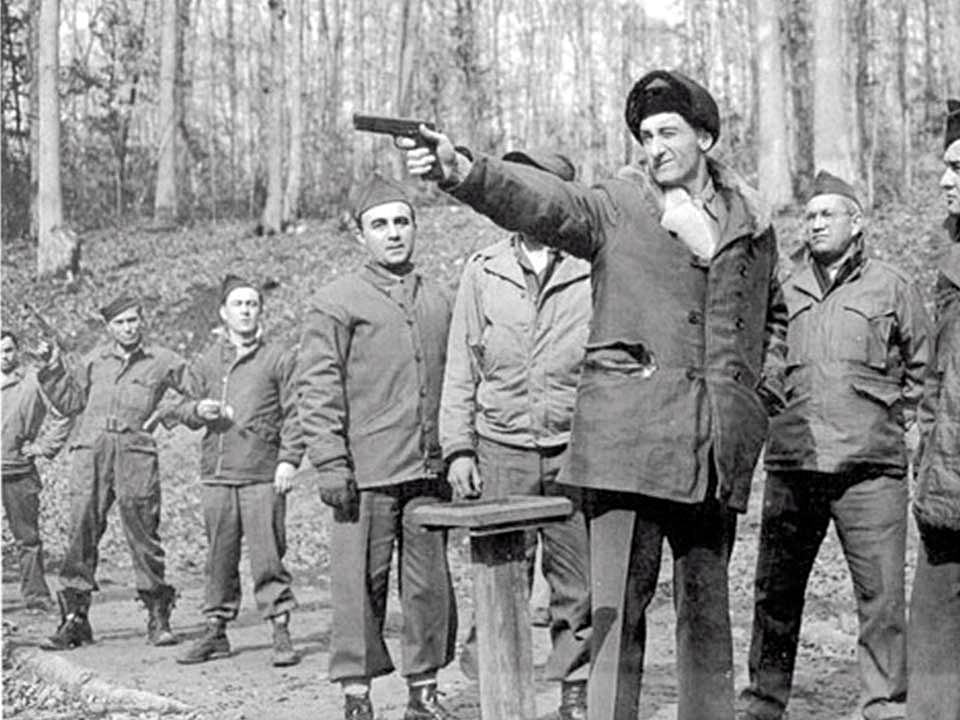

Because of the intense ideological and global nature of World War II, OSS members were required to master tools that were well beyond regular military know-how, such as radio communication, brainwashing, and sophisticated weaponry (Belot, 2002). To do this, Donovan relied on men from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, such as Harry J. Anslinger, to train recruits. Agents had to know different languages and have in-depth knowledge about sabotage, parachuting, hand-to-hand combat, and behind-the-front maneuvers (McWilliams, 1991). Their training depended on the branches to which they belonged. For example, all members of the Operational Groups (OG) had military backgrounds.6 They were trained on using sophisticated weapons and complex guerrilla tactics (Hill, 2013).

OSS operational units were made up of men and women, although the number of men was considerably greater than that of women. While recruits studied at training centers, they had to learn about more than one country so that their peers would not know where they were being assigned (Chalou, 1992). Donovan’s chief psychologist, Dr. Henry Murray of Harvard, noted that the nature OSS work attracted persons with psychopathic tendencies. These people sought sensationalism, intrigue, and mystery (Smith, 1972).

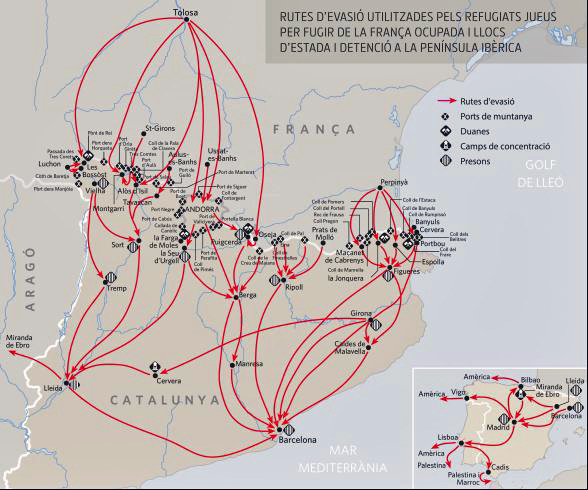

Many people in Spain collaborated with the OSS without forming part of its ranks, including business executives from Barcelona and the Costa Brava, smugglers accustomed to crossing the mountains, and nomadic travelers who knew about clandestine routes. People helped to trace the escape routes through the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean, welcoming the refugees into their homes. The maritime routes were uncharted, whereas the mountain routes were well documented. The little that is known about the first sea routes were those of the beaches of Canet de Rosselló and Port Vendres, near Perpignan (Pla, 2024).

2.4. Escape networks in Spain

This section briefly describes Spain’s refugee routes during the Second World War, how they functioned, and some of their participants. Those routes were located in northern Spain, especially in the areas closest to the Pyrenees. It is well known that, after the Spanish Civil War, thousands of refugees crossed the French border in route to an uncertain fate, sometimes ending in internment, concentration camps, and, in the last instance, death.

The Second World War broke out on September 1, 1939. A few months later, on June 14, 1940, the Wehrmacht occupied the north and west of France, a territory that included the entire Atlantic coast up to the border with the Basque Pyrenees. In the south, bordering the Mediterranean, Marshal Philippe Pétain signed an armistice to establish the puppet state of Vichy, which functioned as a German satellite (Colombo, 1973). Charles de Gaulle maintained the government of Free France in exile throughout the German occupation until Paris was liberated by the Allies in 1944, and a provisional government was reestablished. After the Spanish Civil War, police cordons were established along the borders, including the Gutiérrez Line or P. Line of the Pyrenees, which the Civil Guard monitored until 1955. In 1942, the surveillance zone established by the General Directorate of Security, which had begun by covering the Catalan Pyrenees, was extended to Huesca, Navarre, and the areas bordering Portugal to prevent “the clandestine passage of undesirable people across the Franco-Spanish border” (Sánchez 2003, 63). Anyone over 14 who wanted to leave Spain needed a Special Border Safe Conduct document (Sánchez, 2003). To obtain a 24-hour border pass, several requirements had to be met: first, one had to be loyal to the National Movement; second, they needed to prove their good moral and religious conduct, both in the public sphere and in private life; and third, they could not have relatives abroad who were economic emigrants or political exiles. Women needed the written authorization of their husbands, an exemplary record, and no trace of politically suspicious activity in the family (Sánchez, 2003).

Sometimes permits not only had to be requested to travel abroad but were also required on some roads and railway routes, especially along the police demarcation line along the coast to Palamós—which also passed through inland towns, to Banyoles—and from Girona to San Sebastian: “Upon reaching the designated area for easy, but not free, movement, the bearer had to present himself within 48 hours to the nearest military command, presenting the authorization to stamp the dates of entry and exit. This internal passport had to be shown as many times as required by the authorities” (Sánchez, 2003, 65).

Intelligence agencies and governments from different countries conducted missions in occupied France and Francoist Spain to aid fugitives and help them get to Portugal or Morocco, where they would later be sent into exile in other countries. Through réseaux (escape networks) and ringleras (pathsways) the travelers hoped to reach the embassies and consulates that the United Kingdom, Belgium, and the United States had opened in different parts of Spain, as well as the French Red Cross on Muntaner Street in Barcelona. Once there, railway convoys headed towards Malaga, Algeciras, Gibraltar, and Cáceres to reach Setúbal in Portugal, Casablanca in Morocco, or London by sea. Sometimes the refugees become part of the Free French Forces (FFL) or the American Forces Network (AFN) to help more people (Sánchez, 2003).

Between 1943 and 1944, from thirty to fifty thousand people escaped from France to Spain. Some sources, such as M. Erre René de Ceret, president of the Évadés de France, believed that the actual number of escapees was seventy thousand, thirty-five thousand of whom joined the FFL23.7 As for the AFN, at least twenty thousand volunteers worked, paid by their government and financed by the Americans. Under this initiative, there were passeurs, maquis, mugalaris, and also smugglers. Sometimes they stole jewelry and documents from the refugees, killed them, or sold them to the Nazis. Among its members in the Costa Brava were the Dalí family. Salvador Dalí I Domènech, who settled in Perpignan, passed himself off as a black marketeer who bought Spanish coffee on the edge of the Pertús and betrayed suspicious travelers (Sánchez, 2003).

Documentation was usually falsified in Algerian printing houses. The documents had to show that the person was born in villages, not large cities. In addition, the documentation had to include (a) the street of residence copied from the telephone directory so that it was authentic; (b) a neighborhood that existed before 1943; (c) a description of the person’s face, “showing ages before or after those required to enter the German Compulsory Labor Service”; and finally, (d) the signature of an official, illegible and preceded by the words “l’adjoint-délégué” (deputy delegate). The escapee, for his part, had to memorize some geographical data and customs of the place “where he was supposedly born or lived, as well as the number of inhabitants and the names of the neighbors that he would invent in case he was intercepted at a checkpoint” (Sánchez, 2003, 49).

The guides were both young and old and charged 500 to 1000 pesetas per person for smuggling. Priests and nuns, right-wing people, and republicans all moved together. Older adults, women, and children, especially of the Jewish race, were led through the current Planoles and Nevà because the crossing of the Sierra del Cadí was very long. They were left at the Toses, la Molina, or Ribes de Freser station to catch the Spanish National Railway Network (Renfe) train that would take them to Barcelona via Ripoll. Railwaymen, often Spanish communists, helped to smuggle refugees hidden in freight cars (Sánchez, 2003).

The German army was also vigilant in monitoring the clandestine movements of the Allies and sometimes learned of the existence of groups of Gaullist cheminots (collaborators) with the réseaux that moved refugees. The Comète network was a Franco-Belgian network, renamed by the British as The Dédée Line, which operated from the spring of 1941 to the summer of 1944. It had about 1,700 collaborators and saved 798 fugitives, mostly airmen. Many of this network’s members belonged to Belgian high society. There were also 92 members of the OSS Nana network and Margot, also from the OSS, created by Countess Margarita Corysande de Gramont, representative of the Franco-Navarrese nobility (Sánchez, 2003).

A route also started in Sant Llorenç de Cerdans and reached Cistella, passing through Albanyà. There is evidence of a collaborating switchman nicknamed “el Gordito”. From there, they were taken to the Sagrera station in Barcelona and hidden in neighborhood churches. Around the Port de Salau, which links Pallars Sobirà with the Coserans region in France, 21 Chemin de la Liberté have been identified. The OSS had its network, established in early 1943 under the direction of Frederic Leist, nicknamed “Josep”. This network sent information to the Allies about German troop movements and the location of blockhaus (bunkers) and mines, together with the location of traps and camouflages of sniper nests erected on the Côte Vermella from Argelès-sur-Mer to Portbou. Around twenty people worked on it, including brigadiers and Spanish refugees. One of the routes ran between Forques Ceret, the Pou de la Neu pass, and Maçanet de Cabrenys, with the support of numerous dissidents within the Vichy civil service (Sánchez, 2003).

- Downes served in the Spanish Civil War, supporting the Republican cause. His influence on military decision-making during World War II was possible because he was considered the most well-rounded OSS agent. He believed that the work of the Office of Strategic Services in Europe could be used to overthrow enemy and neutral governments, such as those at both ends of the Iberian Peninsula (Taylor, 2018). ↩︎

- As elaborated in Chapter 3, Melvin Smith Lord and, probably, the writer Josep Pla and his brother, Pere Pla (Pla, 2024), among others, played a crucial role in these networks. ↩︎

- Japan managed its Intelligence Center from Madrid, through a radio transmitter that reached Tokyo (Chalou, 1992). ↩︎

- In Chapter 3, we see that Kurt Walters has a close relationship with Melvin Lord. ↩︎

- Since the American Communist Party sponsored the Lincoln Brigade, the OSS was disapproved of by the FBI and other US government services, as many members of the international aid to Spain between 1936 and 1939 were accused of sedition on their return to America. Likely, they were later able and willing to collaborate with the OSS because Donovan provided them with legal assistance (Smith, 1972). ↩︎

- Melvin S. Lord was probably part of the OG. ↩︎

- At the end of the Second World War, only twenty-five thousand of them would have survived (Sánchez, 2003). ↩︎